Under the Moroccan Sun

For more information about Boar's Tusk, click here.

********************************************************************************

The Moroccan sun met me with its unforgiving warmth, as I walked the dusty streets of Aït Benhaddou with my friend Imane by my side. Imane was Moroccan, with her family living not far from this village. We came to Morocco to explore the Sahara Desert, hike the Atlas Mountains, and see the lively chaos of Marrakech Medina. I thought I would love Morocco for the vibrant culture and astonishing landscapes. At the time, I simply had no idea how life altering the experience would end up being.

We wandered through the qasaba slowly. A few nights earlier, we had spent the night in a riad on the edge of a magnificent cliff hanging off of one of the many Atlas mountains. The traditional village offered me no distractions from the present. There was no phone service to get a mass of notifications, and the village lacked the intensity and hustle of modern life. The night was tranquil. We could hear the Berbers across the street playing loutars and singing tunes in Arabic. We had a perfect view of every star in the vast night sky from atop the riad and we could smell the tajin still in the air from dinner the night before.

I went to sleep that night feeling very comforted by the stillness, but was jolted awake a few hours later by the feeling of being sick to my stomach. Before I knew it, I could not even hold my own head up. I laid naked in the dust for hours, too sick to crawl back to bed. When the sun came up, a man from the raid came to tell me that my bus was leaving, but when he saw my condition offered to send me to the hospital instead. I was delirious, and said I would be fine. I’d never been in a circumstance where my biggest concern was living. I’d never had to suffer through a fever while curled up under the shade of a camel's shadow instead of being inside comforted with blankets and popsicles. He carried me and my backpack to the bus, and sent me on my way.

The next three days blended into each other, each indistinguishable from the next. Gradually, I became well enough to drink water again, then sit up by myself. Soon, I could speak in coherent sentences, and I could trudge around the villages again. And so, we walked through the gasaba in Aït Benhaddou slowly.

(Village Aït Benhaddou)

Imane and I walked around the village, discussing every aspect. Aït Benhaddou had been turned into a filming location, and the people were driven out of their homes. The village only had a couple dozen families left, most of whom were now making money selling crafts to tourists who came through or getting paid small stipends by tour guides to speak and write in Berber languages for the tourists. The unfortunate dichotomy of tourism ruled this town. The people were exploited for their culture and the tourists destroyed ancient infrastructure, raised food and water prices, and ensured the villagers were stuck in a cycle of low income during the tourism months and simple dire poverty during the other months of the year. The income generated through tourism though was the most significant part of the economy. Poverty had a chokehold on the people and their village no longer belonged to them. Our hearts were heavy with the realization of what the Berber village had been reduced to.

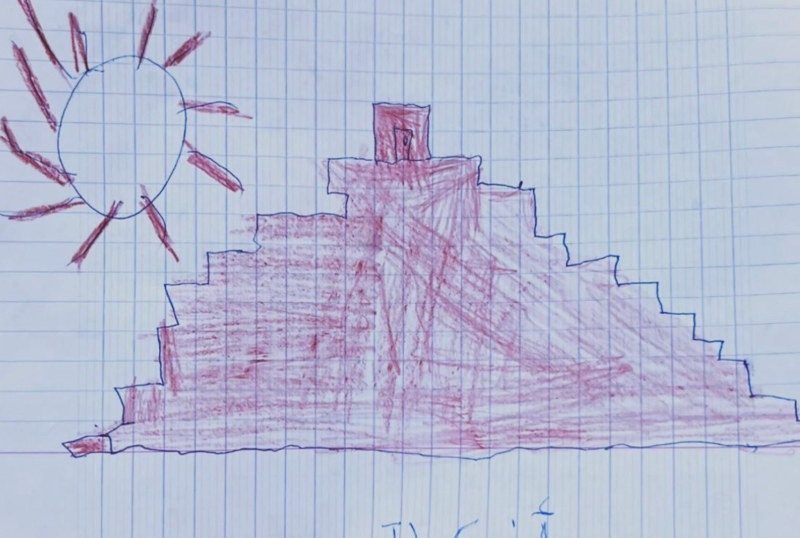

Imane and I continued our wander. Her steps slowed to a stop when she noticed a young boy in the middle of the street blocking the path. He had his head in between his knees exhausted from the heat, but was still alert enough to be startled when he heard us coming. As we came closer, we saw he had a deconstructed cardboard box laying in the dirt in front of him with stones that were holding down pieces of torn out notebook paper. The boy began straightening out the papers and trying his hardest to lock into our gaze. We could tell that he desperately wanted our attention for something.

On the cardboard, the boy had a display of a few drawings, all done with just a blue pen and red colored pencil. I said “hello” to the boy, but he simply continued the eye contact and gestured down at his art. I tried again, this time saying "marhaba," the Arabic word for hello, which Imane had taught me. The boy’s demeanor changed immediately. He gestured to the paper, still silent, but eager for us to notice.

Imane translated for me, and my heart sank “He is selling these pictures to us to buy some things for his family, maybe foods and water. They are all one dirham.”

I smiled at the boy, hoping he would understand that I knew what he had told Imane. I pointed to a picture of the village with the scorching sun in the corner. The boy spoke to Imane, who I presume told him that I wanted to buy it from him. He handed me the picture and I handed him some coins from my pocket. I lightheartedly asked Imane to ask the boy to sign it and add his age—imagining that someday, when he became a famous artist, I would have one of his earliest works. Imane giggled and asked the boy to add a signature for me, but the boy was not sure what she meant. I asked Imane if perhaps the boy was not sure what a “signature” was, and she could instead ask him to write his name. She then told me that the problem was actually that the boy did not know how to write his name, nor did he know how old he was.

The boy’s name was Anar. Imane showed him how to write the characters in Arabic in the dirt, and he copied the letters onto the notebook paper with a pen Imane had in her bag. We thanked him, “shakran,” and continued spiraling up the path to reach the agadir, built atop the hill overlooking the village.

As we gazed down over the village, my mind was racing. Anar was maybe seven years old, but did not know his own age. Did he not know his birthday? Or was the problem that he could not write numbers? If Anar could not write his name there was no way he knew the alphabet. This must have meant he could not read, and perhaps he had never been to school in his life. I didn’t recall seeing any schools in the area, and I understood that it was likely that his drawings were genuinely a source of income for his family, not just a cute “lemonade stand” type of function a child was doing for fun. His future, I realized, was a precarious one—a future where his opportunities were severely limited by a lack of education and access. Of course, I don’t know the exact reality of this child, but I began forming a narrative that told the story of millions of children around the world.

Anar’s story was one telling of a harsh reality: without an education, Anar’s opportunities were limited, and the cycle of poverty would likely continue for generations. I understood then more than ever that education was not just about reading or writing, but about offering a chance to break free from the constraints of an unjust system, like poverty. Anar instilled an unshakable commitment in me to champion education as a fundamental human right. No child should be forced into suffering because of circumstances of birth and access to education can change this.

A few days before meeting Anar, I had been curled up on the ground, feverish and weak, unable to hold my own head up. I had been consumed by my own misery, so desperate for some relief from my pain that nothing seemed more important than just that. Yet, in comparison, to what I saw in the village, my suffering felt insignificant. I had access to food and water, to the comfort of Imane helping me, and I was fairly certain when this was over I would have a future filled with endless opportunity. Anar, sevenish years old, seemed to have had no access to education and no way to break the cycle that kept him trapped in poverty. My wellbeing was restored fully in a matter of a few days. His opportunities, however, were tied to a system far beyond his control. His suffering was beyond physical, and crossed the line in which I now consider moral suffering.

I left Morocco with a renewed sense of gratitude, even after the worst few days of my life and a commitment to dedicating my life to ensuring that others, especially children like Anar, access to education and the opportunities education brings.

(Village Aït Benhaddou, by Anar)

The title “Under the Moroccan Sun” is inspired by Under a Zambian Tree which tells the story of Dora Moono Nyambe and her fight to educate the children of her village. Dora tragically passed away in December of 2024. May it be that her work was not in vain.